Surviving the Struggle: Redefining what Mental Health means in school

February 15, 2019

In just the first semester of my senior year alone, I accumulated 238 absences – I had five classes. In school, my absences define me. I’m known because of them, and they have become my reputation. Last year on Aug. 24, 2017, I suffered my biggest breakdown, where the school filed a missing person’s report, and the next day I was detained by three police cars in the small town of Kalamazoo, Michigan.

My mother worked closely with one of the FBI’s personal investigators, provided by the school, and I was found. My mother recalls how I was completely normal when I hugged her goodbye that morning. However, what she didn’t know was that in the middle of the night I had packed a bag, blanket, pillow and I had never made it to school. All of the police officers knew I wasn’t the type to run away, so I was never questioned. I instead just sat in the passenger side of the police car while I grilled them on their best stories about their time in the field. I debated with them on police brutality, and learned about their captain’s love of his ‘98 VW Jetta.

This was my call for help, and it was rather extravagant, a complete polar opposite for my personality. When I returned home, I was put on medication that was $300 a fill – I called them my ‘super happy pills’. I later learned I was put on these so I wouldn’t kill myself. I also went into intensive therapy, multiple sessions a day, trying to find the why. I was slapped with new diagnoses; severe depression and what my therapist described as ‘paralyzing social anxiety.’

This story is the epitome of why I think it is so hard to seek help, especially in school, and now I live to tell it. I had needed help years before I got it. I used to sit in the back of the class and pretend I didn’t exist, or I’d become a metaphorical barnacle on my friends, essentially using them as a shield from humanity – and I still prefer that route even today.

This school and district exacerbated their resources to get me home, but I had never known resources existed that could have prevented my breakdown in the first place.

It is a fact that the Lincoln Public Schools (LPS) district advocates for mental health, but it is also a fact that most students are not informed of the resources born from that advocation. So this article is for the struggling, the silent and most of all, the educators who pride themselves on their occupation here within the school, but may not know how to extend that pride to a student in need.

“I used to be on honor roll, straight-A student. But then I stopped caring because I wasn’t learning anything. I was just trying to get a good grade,” senior Melissa Ortiz said. “I started skipping because it felt useless to be there. That also brings a lot more anxiety because most students don’t want to go to the office – they’ll avoid confrontation at all costs. So that ends up making it worse. I usually end up skipping in the bathroom or something.”

Ortiz is the co-leader of LSE’s Latino Club and an active member of the new Peer Mediation Group that attempts to resolve student conflicts through restorative justice. Ortiz is also working on a student panel to be broadcasted to teachers about how they treat students regarding their race, mental health, gender and sexuality. To say the least, she is involved.

“I have really bad social anxiety,” Ortiz said. “And teachers do give you a lot of work. They end up caring more about grades than they do actually educating the students to understand the subject, which makes my anxiety worse. And on top of that I also deal with depression. My family is very, very religious, so they don’t believe in mental health. And in general, I’m also just very reserved.”

School, in context, is evaluation. Embedded in a student’s mental upbringing is the assumption that getting good grades equates to immeasurable success. F is for failure, in which we prescribe ourselves to the ideal that failure is a personality trait, and a sentence to a longtime job that festers unhappiness.

It is easy then, to understand why students could see school and the system surrounding it, as a monster. A fault in the system lies when we generalize the 42,000 students in the LPS district with a label to try and stuff them away in a duct-taped box.

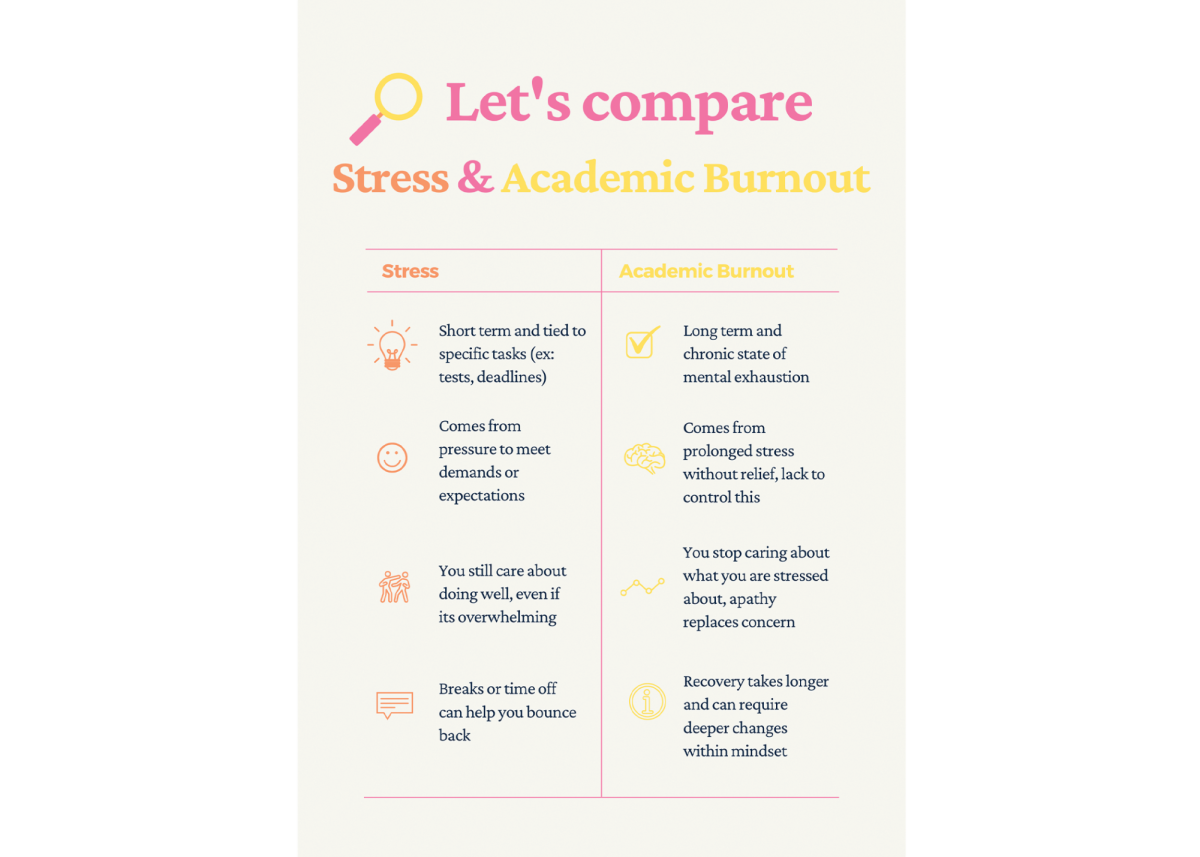

That system fails to remind us of the different circumstances that every student is in. We tend to fixate on our grades, letting our personal worth be dictated by a score. This is the student struggle. This struggle builds and shapes the walls, the lockers, the classrooms into hands waiting to grab and trip us, while our life outside those walls amounts to waiting for the next day of school to start, one day closer to the next break, over and over.

Sometimes the struggle I faced was born out of that hatred for the system or administration, and sometimes– often times — it was a struggle against my own head and my academic work, being overloaded with assignments to challenge my academic threshold. That, coupled with my insufficient study habits, often led to cramming or poor sleep. These struggles led me to my diagnosis.

As this struggle continues, students are perceiving school as a more formidable opponent. On top of that, youth are finding themselves neglecting treatment for various reasons; whether it be internal conflict, stigma, finances or the inability to find it. According to Mental Health America, a nonprofit organization that studies mental health in youth, 76% of youth are left with insufficient treatment or no treatment at all. On top of that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2017, 79% of teachers reported seeing an increase in stress, anxiety and panic in students, as well as a rise in depression, self harm and eating disorders.

Kelsey Lorimer, a former English teacher, now counselor for LSE, noted that the students she worries most about are the ones who stay silent.

“If I get an email about a student from a parent that they had a mental health scare and I have never met that student, that scares me. Those are the students that are high risk because they don’t want help. I think that’s hard to educate, because students are getting better at hiding it,” Lorimer said.

Lorimer switched to counseling partially because she found the power dynamics in classrooms to be too big of a barrier to connect. She felt that these barriers prevented her from helping students, and prevented students from reaching out to her. Lorimer also believes in the importance of exploring education in different forms that may be contrary to the traditional, possibility anxiety-inducing, classroom setting which helped her on her own journey with depression.

“I feel like education can be bigger than just someone standing in front of a class and saying, ‘This is what depression looks like.’ We have the opportunity and space to look for students who connect with literature like Perks of Being a Wallflower, or students who connect with music. Those are things that we need to look for. Students have some way of expressing themselves and we need to appeal to that better,” Lorimer said.

Lorimer knows that students are smart and can know the signs, especially if they’ve struggled with mental illness themselves. She wants students to know that they need to advocate for their friends. You are their best source of information – and your friends’ best allies.

“Talk to us, if you know someone is struggling, we can help them. Students want to hide it because there’s so much stigma attached to it but getting help is always the best option,” said Lorimer.

Getting help is the most important step to recovery, but often times students go through a period where help seems like the last thing anyone wants to give them. Students who are in the grips of a mental health crisis face fear of rejection. That, coupled with a growing sense of worthlessness often makes them feel like a burden to everyone. These internal factors, along with external factors such as bad grades, family conflict and so many more, are often the leading factors of teen suicide (CDC).

Sasha Reeks, a psychology teacher and mental health advocate at LSE, stresses the importance of keeping the conversation alive when it comes to mental health. Because of the stigma and internal battle associated with mental health, a lot of people don’t seek help when they need it. Reeks missed 30 days in the last year due to her own battle with depression and has the courage to share the story of that battle with the students in her AP Psychology classes.

“Attendance is hard. If someone can make it even a couple days, that’s better than nothing, but even that’s still hard,” Reeks said. “[The stigma around mental health] is that you’re ‘bad’ or you’re not as tough as so and so. That stigma is complete garbage. I think lots of times people with mental illnesses are tougher than someone who can cruise through things easily.”

Reeks also believes that expectations should be different for students if they take the time to explain their situation. This is typically common practice throughout the building, yet it is seldom used when needed. Students often feel that a teacher is unapproachable, and that asking for anything is too much work for the teacher, as simple as it may be.

Reeks knows that some teachers will feel that asking for different expectations is not okay, but she is a firm believer that fair is not the same as equal.

“When we’re making something fair for someone to succeed, it doesn’t have to be the same as all the others. The problem is that sometimes people don’t want others to know – judgement is a powerful thing. It’s hard for me to adjust something if somebody isn’t going to come up and tell me why. I definitely think that teachers should change their expectations when people come in and say that ‘hey I have this issue, can you help me?’.”

This isn’t to say that kids who have a mental illness shouldn’t face a challenge, but their biggest challenges may not necessarily be with doing schoolwork, but rather, finding an environment to get that schoolwork done.

LSE Administrator Crystal Folden knows that pushing kids out of their comfort zones can help them grow stronger in their fight against mental illness. Folden reminds students that hitting rock bottom is okay, and oftentimes necessary, for them to grow and recover.

“You can either live with [anxiety and depression] or you can figure out how to stop letting it control everything. And no one says it’s not hard, and I would never ever claim to say that. It’s a fight, a constant fight,” Folden said. “It’s a fight where there aren’t many other options. You can either live in this constant stupor or you can get up every morning and practice the strategies your therapist taught you.”

Folden works with many kids who struggle with attendance and behavior within Southeast, and she always asks, ‘what are you doing today that’s different from yesterday?’. She knows a lot of students don’t focus on that, and instead linger on the feelings that may metaphorically eat them up inside, but her end-goal is always for them to graduate.

“That’s the hard part, and I’m not saying that’s easy – I’m just saying that we need to realize our maturity level,” said Folden. “You don’t immediately get to see the payoff, and so many kids are stuck on wanting that payoff. I think that when kids get a little more mature, they see that. So I just keep pushing them.”

Kids often go through their own forms of hell before they get better. What most students don’t realize, though, is that this is a fight they shouldn’t face on their own, even though that seems like the safest and most comfortable option.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), 1 in 5 youth, ages 13 to 18 will experience a severe mental disorder. In just the last year, 1.8 million youth suffered from a diagnosed mental illness, and NAMI states that there are probably hundreds of thousands more left undiagnosed. We often forget that mental health conditions don’t just affect individuals who have it, but touches everyone who knows and loves that individual. It is unrelenting – and medication alone isn’t always sufficient.

What helps is talking about it. Opening the dialogue on mental illness makes its existence okay – and one step closer to erasing the stigma or someone finding the courage to seek help. NAMI started the CureStigma Movement in an effort to eliminate said stigma. They conducted an experiment, traveling to high schools in several states, asking students to raise their hands if they, or anyone in their family, struggled with mental illness. “Almost everybody raised their hands,” Alexandra Von Plato, their President, said. “They had no idea; they thought they were the only ones.”

Pinpointing a single solution to end the struggles of mental health is nearly impossible, but through starting the conversation, we’re not avoiding the idea as a whole. Moreover, as we gather more insight and personal experiences, we can learn how to better accommodate to students in need.

“I think one of our main issues is avoidance,” Lorimer said. “That’s a go-to for people who are anxious or depressed. There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to anything. Like with the ‘Keep Calm and Stay in Class’ poster, it has strategies that work for some students, but also strategies that seem like some kind of joke to others. So that’s hard. Working as a district to help figure out how we can help students of all mental health situations is crazy-hard, but we’re constantly working on it.”

Even taking that into consideration, the biggest problem that I found in the course of writing this story, interviewing every figure on the chain of command, was the fact that there is a ravine-sized gap between faculty and student communication.

Whether it be the unfavorable 2013-esque, ‘Keep Calm and Stay in Class’ posters, reminiscent of my ‘Keep Calm and Young Life On’ t-shirt, a statement piece I wore in middle school — or the unappealing, definition-driven, non-engaging powerpoints with absolutely no personal-anecdotes from counselors or students, the resources provided are not being (properly, if at all) conveyed to students.

Deep in the tresses of the LPS website lies the ‘Student Services’ tab, placed in an indistinguishable spot near the bottom of the page in a section dubbed specifically as the ‘Parent Center’, where, most likely, a student will sort through PDF documents and end up confused even further about where to go next.

The district is aware that this is an ineffective method, but as the years pass, changes are practically microscopic to students and thus, they still continue to struggle. This isn’t to say that these resources don’t exist and expand yearly, it’s just that the district doesn’t actively take enough time and consideration into asking viable students their honest questions about what to do next, and students don’t necessarily see the district as approachable. It’s not designed to be. A student ends up having to step through multitudes of bureaucratic hoops to get to an actual policy-changer.

However, small changes are still made in the Southeast hallways every day, especially by those who experience first-hand the hustle and bustle that is our five minute passing periods. Heidi Moore is the Special Education Coordinator here at Southeast. She works closely with Kelsie Banks, Assistant Special Education Coordinator. The duo can be seen perusing the hallways of Southeast during passing periods with only one goal in mind: to make the hallways as safe of an environment as they can be.

Moore and Banks alike love bonding with kids. Moore strives for having only positive encounters with students, and Banks has a goal of trying to learn every student’s name. They both possess big hearts and a love of their job, as hard as some days may be.

“We’re not here to tear people down, we’re here to get an education and I don’t want harmful words to be the reason that deters someone from that,” said Moore.

What Moore is talking about are the insensitive things said in our hallways every day, often overheard. Because of these things, students can feel alienated and ostracized for things laced within their core identities.

“Every student should feel safe and worthy and comfortable exactly as they are. So if I do hear something negative, I always address it and try to come to an understanding with that student,” Banks said. “Through broadening their perspective we’re able to change it from something like a slur to a statement that is respectful of the people in this building.”

Through their efforts, Moore and Banks have been able to connect with many of the students at Southeast. Whether it be a high five, a compliment or a simple gesture like asking how students are, they’re making a difference.

“I think as educators we forget how valuable of a resource we are in ourselves. The little deposits we make on students can impact them so heavily in the bigger picture,” said Moore.

Moore also notes the importance of having a trusted adult in the building that a student can go to for support or otherwise.

“There needs to be a change in our own mental model of a classroom. We tend to be drawn to that sitting in a chair, raise your hand to speak, when it reality, that feels like a confine for most students,” Moore said. “I’ve gone to a place where I might not be super comfortable, and when someone does something so simple like say good morning, I’m glad you’re here, it changes the feeling of things.”

Banks notes how she doesn’t get to see everybody all day long, so she also sees value in the small interactions she has with students daily, and says those interactions can make them feel just a bit more welcome.

“Sometimes students deal with things that you can’t even imagine, you know. They need someone to talk to, or to care about them. I always want to make a point to ask,” Banks said.

Escaping the confines of the common classroom can be the goal set as soon as a student walks in or out from passing period, mental illness or not. In my personal experience, I used to plan escape routes or excuses to leave in my head to try to delay my own exit from a classroom just a bit longer so I wouldn’t feel as guilty trying to skip. Silence in class was particularly excruciating. For a kid with severe anxiety, silence is like having a red dot placed right on your heart by the S.W.A.T. team.

So where can you go if you need to calm down? Usually the most opportune places are the bathroom or one’s own car – however, those aren’t the best options, and ultimately damage your education in the long run if they become routine.

“I wanted to see if I could get a room for if a student was having an anxiety or panic attack, or they were going through something, somewhere they could go. The problem with that was that some kids would actually take advantage of that room and skip school,” Ortiz said.

Kelcy Sass, the head of the Counseling center recognizes that struggle, and has tried to find a balance that helps to work around it.

“There’s times where kids want to just come and hang out and avoid, and that’s really hard because we’re compassionate people,” Sass said. “We want to make it comfortable for kids. But sometimes, you have to face some of those difficulties, we have to be uncomfortable.”

Sass, among all other counselors, want students to know that the Counseling Center is still always there to help, and if you need it, they’ll give you some space to just sit and breathe.

“I think one of the things we want kids to understand is that we have lots of resources and experience with students who need help. We want them to feel comfortable coming in and sharing that with us, and just being you,” Sass said.

The Counseling Center and administration together work hard on creating and finding solutions that help students. The staff in there are trained and there to help – all they need is a go-ahead.

“It’s part of our job as educators to help students understand why we’re asking them to do certain things,” Sass said. “Or why maybe they will feel more success following a certain new and scary action. I hope that by us explaining to them the process, it would help them, not scare them away.”

Gretchen Baker works closely with the students at Southeast, having taught in the LPS district since 1999, and LSE since 2011. She often coordinates with her colleague Morgan Young, another social worker at the school, on finding and creating plans for struggling students while also letting the student know that they’re welcome there.

“Most of it is really brainstorming, and letting them pick what works for them. I want to encourage them rather than stuffing it down, and [students rely on their] peers a lot but I would encourage them to always have an adult,” Baker said. “A lot of kids don’t have that because they’re very fearful of that.”

Baker also wants students to know that by coming and talking to a counselor or social worker, your relationships with peers and teachers in the school are not going to change – and they don’t intend for them to.

“It’s on us to educate the teachers on when to pass situations onto us, and what that does not mean is that the teacher then has to stop talking to you. We’re both going to talk to you,” Baker said. “I think sometimes students and teachers worry about what our role will be like – where people think they can only talk to us. But that’s not true, we have to get rid of that misconception. We’re just an added layer.”

Young has created and continues to foster partnerships with local community-based organizations that work to help students with mental health issues around schools.

“What’s vital for me is figuring out how we can better support students and get them to come to school, and make them want to be here. How we can figure that out so they can graduate,” Young said. “I teach a class called ‘Why Try?’. It’s not super mental-health based but it’s basically about finding your motivation to come to school, and why you should care. It works on identifying the supports you have and how to use what’s available to you.”

Young and Baker work collectively with all other social workers in LPS to decide on information to be presented to faculty. This can differ school to school, and as more issues present themselves, more information is added. The issues aren’t cycled through either, but rather added to a collective pile for distribution.

Russ Uhing is the boss of all 41 social workers in the LPS district, a job which he does not take lightly. Uhing was a former teacher at Lincoln High School, and is now the director of Social Services for the LPS school district, a position he has held for over seven years.

Uhing is an advocate for the expansion of mental health programs across LPS. He has worked closely with the Board of Education on expanding funding and awareness so students have resources available to them to be used at their discretion.

“We want to continue educating everyone about mental health, because just like physical health, there are preventative things we can do to benefit a student in the future as mental health becomes more prevalent,” Uhing said. “We also want to have systems in place to where, whether it’s the building or connecting with community resources, that if a student needs more, that they’re able to get more so they can be successful in school.”

Uhing notes that the efforts are not being made in just Lincoln alone. As the stigma continues to weaken across the US specifically, more and more people are talking about mental health.

“The resources as a district that we have put towards mental health has grown tremendously,” Uhing said. “Our goal for all students is to be successful in school, and also be prepared for life outside of school — whether it be employment, military or post-secondary education.”

Uhing knows the details in which the district has expanded on, noting how they have dramatically increased their number of in-district mental health resources as well as their connections with community partners.

The district went from 5 to 19 elementary school counselors in just five years. This is to help prevent the onset of mental illness later on. They’ve also increased the number of school psychologists to over 40, and have partnered with HopeSpoke which is in 18 schools, Family Services in 30 schools, including Southeast, and Blue Valley in 17 schools.

“Now we have about 80% of our schools with community therapists in the building, where students have their own individual therapists,” said Uhing. “We also provide mental health services for our refugee and immigrant population because many of those kids who come to us have experienced significant trauma.”

Uhing notes how practices differ from school to school, even as policies stay the same. Practices are suggested methods of operating while policies are required. Most of the practices within Southeast to accommodate varying situations are through the Student Assistance Process (SAP). In short, the SAP is an individualized plan corroborated with teachers to meet a student’s needs for success. Steps further would be an IEP or 504 plan, to be discussed with a counselor and administrator. Information on these plans can be found under the Parent tab on the LPS website.

“We always have more work to do. We’re certainly not where we want to be because that’s always growing and changing. As a school district, as a community, nationally,” Uhing said. “This is an issue that we don’t devote enough resources to, but we are making some changes going forward.”

So how can you make a difference? Students – advocate for yourselves. You are brave, and anyone you reach out to knows that. Teachers – advocate for your students, educate yourselves. Make sure students know about the resources that are out there, and understand that this isn’t something you can just skip over. And to the counselors and administration – get out there more, talk to students, seek opinions, find ways to grow and appeal to all students within Southeast.

You could be the reason that a student decides to walk the halls another day, wears a smile on their face, comes to class, or decides that they are worth something. The reality is that so much of life is based on the connections we make and realizing that there are people there that actually care for us. We don’t take the time to realize that the small steps we take leave big impressions for others. And above all, it is okay to have needs. You are not a burden. We are all human and understand your struggle.

Help is out there, and don’t wait – you matter more than you realize.

National Suicide Prevention Hotline:

1-800-273-TALK

LGBTQIA+ Hotline:

1-800-398-4297

Eating Disorder Awareness and Prevention Hotline:

1-800-931-2237

National Domestic Violence Hotline:

1-800-799-SAFE

Youth Crisis Hotline:

1-800-448-4663

Self-Harm Hotline:

1-800-DONT-CUT (366-8288)

Addiction Hotline:

1-800-662-4357

For Text:

Text HELLO to 741741

Southeast is now home to an in-person one-on-one therapist, Nicole McGuire. Talk to your counselor if you would like to discuss seeking in-school help.

BetterHelp is an online text, video or call e-therapy subscription that matches you with a licensed therapist. Plans start anywhere from $40 and can extend up to $80 weekly payments. It is 80% cheaper than the average psychologist.

Talkspace is a similar e-therapy site with access to licensed therapists 24/7. Plans start at $45 weekly. It is significantly cheaper than the average co-pay insurance plans with a licensed in-person therapist.

Both of these services can be cancelled at any time for any reason.