Words can hurt– combatting the use of hate speech by peers

March 22, 2021

At the beginning of her 7th grade year, Layla Riley (10) transferred from a racially diverse school to a predominantly white school where she was approached by students asking for the

“n-word pass”. Surrounded by students she had little in common with, as a way to fit in she would often say “yes”.

“They took my vulnerability and used it as a way to consistently say things like the n-word [a racial epithet historically used to dehumanize members of the Black community] carefree,” Riley said. “And when called out on the use of the slur, the response was ‘I have the n-word pass’.”

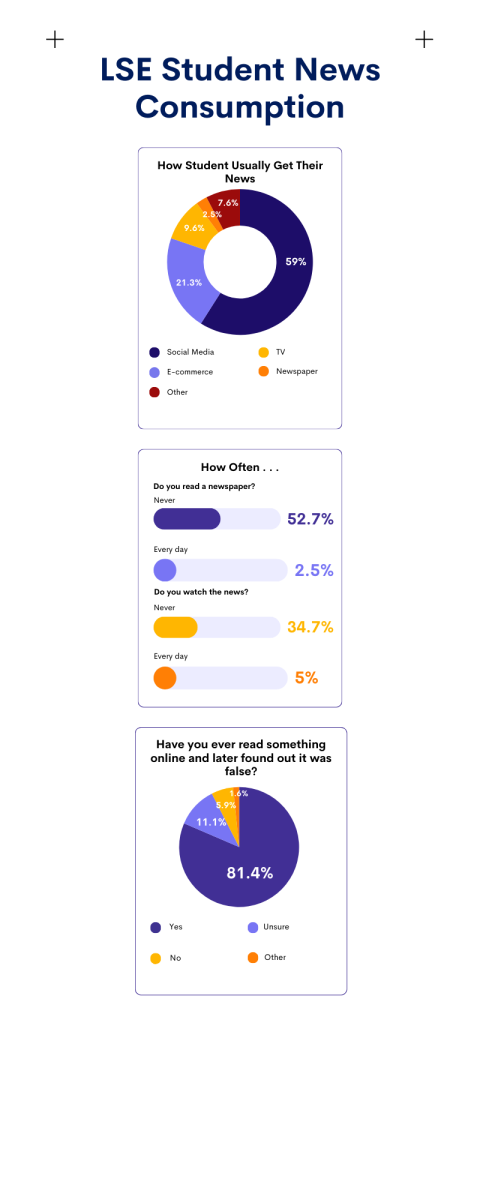

According to a Clarion News Team survey of 113 Lincoln Southeast High School (LSE) students, 66.7 percent frequently hear others using slurs, with 33.3 percent saying they have been called a slur at least once and 12.6 percent saying they get called a slur all the time.

Vann Price, the newly appointed Lincoln Public Schools (LPS) Director of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, said her department takes a specific course of action when hearing of situations similar to Riley’s. Consequences for violating the LPS code of conduct–including using hate speech–can be determined based on the “Responsibilities of Students” document. Price, who formerly was principal of Lincoln North Star High School, says that generally, breaking these rules is taken very seriously, but administrators must also perform an investigation into the circumstances to ultimately decide where to take it from there.

“I think there are some [circumstances] that potentially are a bigger deal than others, and I think that’s why we just don’t automatically jump to the consequences. We have to know particulars,” Price said.

Some examples of things that have to be considered to determine the next course of action are whether the intentions were deliberate and were intending to bring others harm, if it was an act of ignorance, if it was passing on something that was sent by a friend, etc.

Case-by-case, punishment can include: suspension, an in-school administration-supervised plan or even expulsion.

Price says that she thinks teenagers often say things without realizing the potential consequences until they see other’s reactions. She is a firm believer that people, especially teens still learning to navigate this world, make mistakes and can learn from them.

“What’s most important is that students walk away feeling like it’s an opportunity for them to grow. Yeah, they made a mistake, but we want them to learn from that,” Price said.

In response to recent events, many young advocates like Riley have been working to condemn the use of any form of hate speech, no matter the intentions. Since Riley’s middle school days, the use of the n-word by anyone who is not a part of the Black community can lead to them being “canceled”, or shunned on social media as a result of saying or doing something controversial.

From Price’s perspective, although ‘cancel culture’ can be effective in pressing people to take responsibility for their actions, the internet sometimes tends to remove the human aspect and continues a cycle of hurting others.

“Sometimes social media is just intended to inflict harm and to continue hatred,” Price said. “So if you are continuing to spread hatred and those kinds of things, I don’t think that’s beneficial, and the educator in me always wants to make sure that there’s an opportunity for students to grow and to learn, but also be held accountable for their actions.”

Advocates hope that, with more education and awareness on the history and harm of the n-word, its use in schools will continue to decrease. But why does using that word often have a much greater punishment than the use of others?

75 percent of respondents to the Clarion survey said there are some slurs that are worse than others, and when asked to elaborate, most believed the use of the n-word should be taken more seriously than others.

Price thinks that the reasoning behind this conclusion is because of the historical context of the word.

“It’s always been used as a word to inflict pain, whether it’s physical or mental, on other human beings, and just to really make them feel less than human,” Price said.

Respondent to the Clarion survey Nick Herbin (10) also feels that it’s important to consider the historical background of words. For example, he said the f-word [historically used against members of the LGBTQ+ community] or the n-word have been used for a very long time to hate on that particular group of people, while the r-word [historically used against those in the special needs community] was a term developed for clinical purposes in the 60s before it became an offensive word used in casual conversation.

“So that’s two very different ways of starting the words and using them,” Herbin said. “Obviously there isn’t a huge difference. A slur is a slur, and slurs are not okay to say in any circumstance.”

Riley believes all slurs are equally damaging, due to the fact that the use of any slur can cause equal amounts of damage to the respective community they pertain to.

The majority who responded to the survey said that they heard hate speech most commonly from peers in an attempt at a joke or an epithet–a word or phrase that describes a characteristic of a person or thing mentioned.

“Usually I hear it jokingly or as a greeting,” Riley said. “Like when the boys [a male friend group] are trying to be funny to their friends, [they’ll say] ‘no homo’, or ‘that’s gay’, or just things that have no connection [to the original meaning of the word].”

Riley thinks that it is important to understand it’s not a matter of whether the intentions of using the word were to cause harm or be funny, it can still be hurtful to the community the word pertains to.

A commonly used example of a discriminatory epithet is calling someone the r-word in an attempt to be used as a synonym to “stupid”. This use may not be directly used to harm people that the word was originally used to target, but it still contains a negative connotation with the use of the word, which results in indirect discrimination against that group.

Price thinks slurs and epithets similar to that should be avoided regardless of how one uses the word.

“I think, in my opinion, it does not make it any less wrong, depending on who’s standing there. The word is just wrong,” Price said.

A common circumstance where slurs are more acceptable is when they are reclaimed by the target group to express solidarity and pride. According to the 2013 journal article “The Reappropriation of Stigmatizing Labels” by the Association For Psychological Science, research found that those who did this “felt more powerful after self-labeling, and observers perceived them and their group as more powerful,” which led to a decrease in the negative connotation that was affiliated with the word.

However, reappropriating derogatory words is a personal choice made by individual members of the community, and some may choose not to. One respondent to the survey, and member of the LGBTQ+ community, chooses to avoid using any derogatory terms regarding their community with the belief that their predisposition to their personal identity doesn’t affect the fact that the word is harmful.

“Once one truly finds out the hate a slur bears, the history contained within that particular slur, that person won’t use it,” the respondent said.

Price agrees with this, saying that she stands against the use of slurs regardless of who’s saying them.

“When I was a principal at North Star, I would call students on the use [of slurs],” Price said. “[Even if] it was a group of young African American men that were standing and talking and may call each other [the n-word], I would stop them and say ‘No, that’s not a word that we would use at North Star’ because I am of the belief that the word is just filled with hate, even though sometimes students are not necessarily understanding that or intending for that to be the case.”

Riley believes that in order to combat the use of these damaging words, people must take it upon themselves to do better.

“I would say [the solution is to] educate, but it is never anybody’s job to educate those who don’t want to be educated,” Riley said. “Not tolerating [the language] or telling a trusted adult when hearing a slur can help tremendously. And it can make those around hearing the slurs that may pertain to their community feel more comfortable, and it could help them feel less unheard.”

Riley believes that schools need to start a conversation, and people should go out of their way to learn the history behind these words. Something that could help, Riley said, is that the education system could explore the history behind slurs and how language has been used to marginalize and malign different communities. She thinks the school history curriculum fails to discuss the emotions behind the events, which prevents full understanding of the pain behind these words.

“They may still not understand how deep the stories are because, as much as history can talk about the events, they can’t really teach the feelings of certain people,” Riley said.

Herbin says that resistance is key to combat the use of slurs by peers.

“Stand up to it. You’d be surprised how some people are willing to change when met with resistance,” Herbin said. “Whether it’s a joke or meant to get a reaction, don’t feed into it, don’t allow yourself to show any reaction or pleasure from what is being said.”

Price says that students right now have more power than anyone to enact real change.

“Young people are the ones that are going to make the difference. Your generation has to be willing to take a stand and say ‘this is really important that we all understand this’,” Price said.

She thinks that the eradication of hate speech from everyone’s vocabulary would provide for a much safer and more comfortable environment for all.

“I think that any time we are able to take hateful language out of our vocabularies and replace that with positive words, words of affirmation, words of encouragement, that helps all of us,” Price said.

If you experience any form of hate speech towards you or others, visit LPS.org and click on the Equity Concern tab. This will allow you to navigate to a place to express concerns about an incident and then the Multicultural Department will take it from there.