IMPOSTER!

Imposter Syndrome is causing an outbreak of unworthiness

graphics by Ksenia Gevorkova

December 9, 2021

In 1978 psychologists Suzanne Imes and Rose Clance first identified a feeling that was mutual for people across the globe. In this phenomenon, individuals experience feelings of inadequacy that occur despite high achievement and decorations to prove their success. This notion was coined “imposter syndrome” and has affected over 80 percent of the world’s population with one in five high school and college age students experiencing this syndrome, according to the “Best Colleges” website.

Global Management and Leadership Coach Gill Corkindale for Harvard Business Review states that these individuals are proving to suffer from “chronic self-doubt and a sense of intellectual fraudulence that override any feelings of success of external proof of their competence.”

For senior Lily Rippeteau (17), her experience with the imposter affliction mirrors the same descriptions that life coaches, scientists and psychologists are deducing.

“It’s this strange dynamic,” Rippeteau said. “I think and I understand that I have a lot of talent and I believe that I’m worthy of being in those places, but I still get the feeling.”

Rippeteau, who is involved in many activities both in and out of school, has quite the record to show for her achievements. This semester alone, she is enrolled in five advanced placement (AP) courses while balancing tennis, sailing and working throughout the year.

While it can be stressful at times, she says that she finds a lot of fulfillment from working towards her goals.

“I like doing things that are hard because I know that they’re gonna challenge me,” she said. “I’m prepared to feel confused and scared and lost at times but I know that I will get over that. [When I do] it’ll feel so incredible.”

While she has the talent and training needed to participate in everything she does and applies for, Rippeteau still suffers from not being enough.

“I have work experience, long term sports commitments, leadership positions, I have the qualifications but I still get that moment of [feeling] like there are other people who are more worthy of this than me,” Rippeteau said.

One vehicle in our modern age that has allowed comparisons of achievements to become more prevalent in our everyday lives has been social media.

Just Mind published an online article discussing the different types of comparisons one might make while scrolling through an app’s feed.

Professional counselor and writer for Just Mind, William Schroeder says the main type of comparison linked to imposter syndrome is referred to as an “upward” comparison. Here, “we compare ourselves to others who are where we’d like to be. The problem is that it can easily make us feel inferior, and with social media, we can feel completely overwhelmed by the amount of comparisons that can be made,” he said.

This basis is one of the main reasons Rippeteau chooses to steer clear of social media.

“I do not look at instagram, I use snapchat to text people when I need [to], but I do not look at stories because I have recognized the way that they make me feel invalidated. They make me feel less than people; they make me want things that I don’t genuinely want, but I want them because of the design of the app,” she said.

Her experiences arguably represent how the rest of the online generation feels. Celebrities in our current culture are recognizing how insecure even the most ‘ideal’ of body types and personalities can be due to the social media craze, resulting in dramatic changes to their character. Singer songwriter Selena Gomez has expressed many times how social media has affected her mentally and the negative effects she experiences because of it.

“Everybody has things that they aren’t confident about and I’ve really started to recognize that. Everybody else has those insecurities and the feelings of unworthiness like that is such a human feeling,” Rippeteau said.

However, she recognizes that social media spaces are built upon feelings of insecurity, and will ultimately amplify feelings of unworthiness or lack of confidence.

While one might interpret these feelings to be a starting foundation for developing imposter syndrome, LSE Senior Adam Algahimi feels as though the upward comparison is something that could push individuals to get better.

“Imposter syndrome goes hand in hand with competition,” Algahimi said. “[Competitive people] like to gauge how [they’re] doing based on how the people around [them] are doing.”

To him, imposter syndrome is seen as an opportunity for growth if handled in the correct manner. Instead of feeling sorrowful, bring out that competitive nature and use it for growth.

“If you’re feeling really competitive then set them as [an] expectation [to] meet them,” he said. “It’s what you ended up learning, not what the people around you ended up learning. If you focus on [the opportunity for growth], then you’ll probably get a lot further.”

The aspect of comparing oneself to others is exactly what imposter syndrome is based on. While some, like Algahimi, find ways to pull positives out of it, Rippeteau is prompted to dig deep to realize her motives for her success.

“Re-evaluate why you’re doing these things. Are you doing it for other people because you feel like you have to measure up and to be worthy, or are you doing it for yourself because you want to,” Rippeteau said. “I do my best to recognize that my external success is not what I’m working [towards]. I’m working for the internal drive because I want to work for things because that makes me feel good- I like learning, that’s why I’m in these places, not because I have to perform for other people but because I genuinely want to do it for myself.”

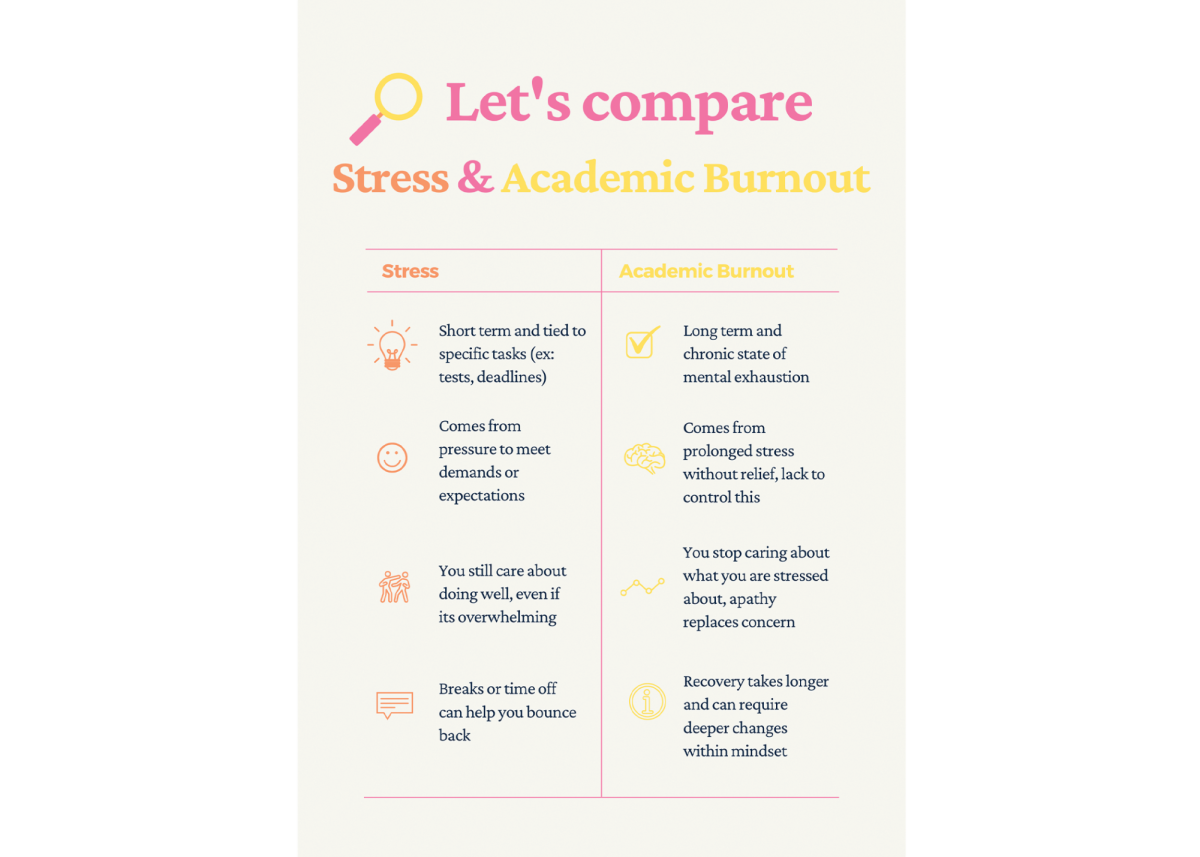

She finds that when individuals begin setting personal and educational goals for others, it leads them down a path that is closely related to gifted burnout, where internal validation is based solely on the thoughts and feelings of others.

To stop these feelings of unworthiness or invalidation, in either case, Rippeteau suggests looking towards a clock for guidance.

“How long have you been feeling this way? When you’re feeling insecure, it feels like you’ve always been that way a little bit.” Rippeteau said.

In addition, she always reminds herself that “This will pass. It allows me from not letting that perspective cloud what’s happened in the past or what’s going to happen in the future because it’s how I feel right now and that’s okay.”

Rippeteau’s use of meditation in her everyday life is something she utilizes in times where imposter syndrome might be getting the best of her.

“[After] taking my attention to something else, like deep breaths, I realize that I am okay, these things are not in control of me and I am making the decisions here and I can decide not to let them stop me.”

Regardless of what the situation is or who is involved, there’s a good chance that imposter syndrome is going to be a main player. For Algahimi and Rippeteau, both see the negatives towards the invalidation that comes with the ailment but find that there are some positive results as well.

Algahimi believes that “A little bit of imposter syndrome is always good. It’s good to have to feel like you can always do better and you can strive to learn more.”

For Rippeteau, she enjoys being around people she has respect for. “I want to be around people who have things that I admire [and] are cool, being around those people makes me a better person. They have skills [that] I can work with [to] create something that’s really cool and really big. These are the people I want to be around.”