Disclaimer: The Clarion recognizes the difference between sex and gender. In this story, the word “woman” is used to refer to biological females, for the sake of understanding and to reflect the terminology that was used during that time period.

“It’s not hyperbole to say that Meg Crane literally changed the world with this invention [of the at-home pregnancy test].” Timothy Scholl, the Executive Creative Director of Angels Theater Company, a non-profit in Lincoln, voices the perspective shared by many. While a considerable amount of people (90.7% of respondents to a survey of LSE students and staff) have never heard the name “Meg Crane,” much less her profound and inspiring story, chances are she’s even changed your life. Whether it be the precedent she set for the at-home Covid-19 tests we’ve all become familiar with or her actual invention, the at-home pregnancy test, Crane has changed the world. So why isn’t “Meg Crane” a household name?

Crane was a product designer for a pharmaceutical company in 1967 when she was inspired to create the at-home pregnancy test after seeing the lab-based ones at Organon Pharmaceuticals, where she was working at the time. During this time, credited as the “dawn of the sexual revolution” by a New York Times article titled, “Could Women Be Trusted With Their Own Pregnancy Tests,” women needed to visit a doctor to be tested to see if they were “with child” (the word “pregnant” was considered inappropriate.). These tests would be sent to a lab to be evaluated, then sent back to the doctor, and finally, the woman would be informed of the results at her next doctor’s visit. The at-home pregnancy test would eliminate any outside intervention from doctors, husbands, boyfriends, or parents, which was liberating for the women of the 60s. However, the company that Crane worked at wasn’t initially in support of this revolutionary idea because they didn’t want to align themselves with “the fast women who desired a fast test,” according to the previously mentioned Times article.

Eventually, without Crane’s knowledge, her boss planned to go forth with the at-home test and a meeting was held with other product designers. Crane did not receive an invitation. The prototypes presented had tassels and flowers, very much contrasting with Crane’s minimal design. She attended the meeting without being invited and eventually, her prototype won out. Crane’s name is on the patent for the original at-home pregnancy test, although she never got any money for her invention.

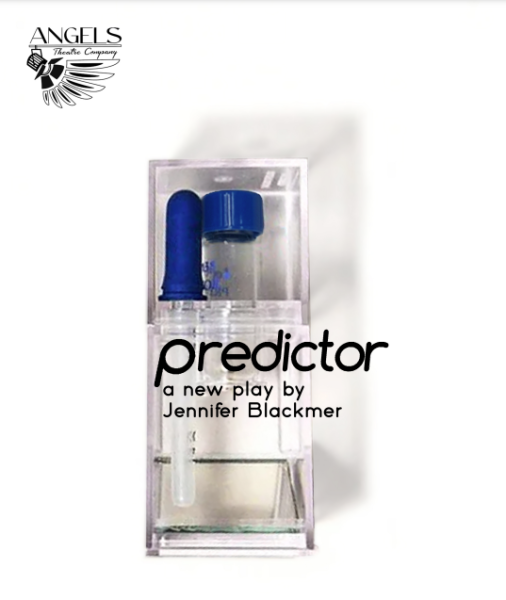

Currently, a play put on by Angels Theater Productions called “Predictor” is finally bringing Crane’s story to the spotlight.

“I think this is a really important play in our world right now and it’s an important conversation for us to have in our community,” said Scholl, who is also the director of the play. “As a society, we are again facing questions about who controls access to healthcare. . .this is a conversation we must have to develop as a healthy and mature society.” The play, set in the three-second timeframe it takes Crane to sign her rights over to the company for a patent to be officiated, chronicles Crane’s life and the process it took f-

or her invention to make it to production in the United States. The playwright, Jennifer Blackmer, also uses this play to demonstrate the stigmas and stereotypes about women that dominated life in the 60s, using artistic variations of real-life advertisements to achieve this. Viewers of the play watch “talk shows” and “advertisements” during the play that concern pregnancy (the word “enceinte” was used in place of “pregnancy” during that time) or menstruation (which should never, ever be spoken about in public). “Predictor” plays on people’s emotions, making the audience both laugh and cry throughout the roughly two-and-a-half-hour running time.

On Saturday, February 11, a talk was given between Meg Crane herself and audience members after the performance, where some people shared their own experiences using Crane’s original pregnancy test some forty years ago. Others were so moved by the play that they were inspired to start a petition to get Crane the money she never got for the production and distribution of her test in the 70s and 80s. Crane herself revealed that the biggest impact that Predictor had on her wasn’t the test itself, but the man she met. An adman hired to manage the marketing of the at-home pregnancy test, Ira Sturtevant, and Meg Crane fell in love during the process of producing Predictor, although they never married or had children. Crane also shared, specifically directed to young women of this day and age, “Be very true to yourself. . . think about your future in a way that’s going to be a wonderful, productive one. . . and read a lot of books.”

25.5% of survey respondents that are biologically able to become pregnant have taken a pregnancy test, demonstrating that the invention of the at-home pregnancy test has directly impacted a significant amount of today’s population. This number doesn’t even represent the number of people who have been indirectly affected by Crane’s invention, by knowing someone or being impacted by the positive results, known in today’s day and age as “two pink lines.” So how come the Predictor isn’t treated as a staple in the inventing and science communities? Many attribute it to the stigmas around pregnancy and sexual education. While not as extreme as the 60s may have been, these stigmas are still prevalent today. In fact, more than 56% of survey respondents agree that pregnancy tests and contraception are stigmatized in a high school environment, and even more so in the larger scope of society as a whole.

These stigmas surrounding subjects that have been deemed “innapropriate” by society, while harmful overall, can lead to the obscuring of moving and important stories such as Meg Crane’s. They can also make people feel shameful and uncomfortable to share parts of their own stories or private lives, which is a contributing factor to the appreciation and happiness that the private, personal at-home pregnancy test was welcomed with. Furthermore, these stigmas can work their way into education; over half of the survey respondents said that their experience with sexual education within LPS hasn’t been adequate, with some specifying that their learning covered the basics, but not every thing that a high school student should know.

While stigmas and stereotypes are a concept that will always be around, groups and people like Angels Theater Company, Her Voice Matters, Jennifer Blackmer, and others are working to combat those and make the world a more comfortable and safe place for people to share their own experiences. As Scholl says, “This is a really important play and a really important story for young people. . . Theater places you in front of a person and asks you to see the world from their perspective . . . [that’s] what the theater is powerful, and it is why I believe this story deserves to be told on the stage.”