By: Olivia McCown –

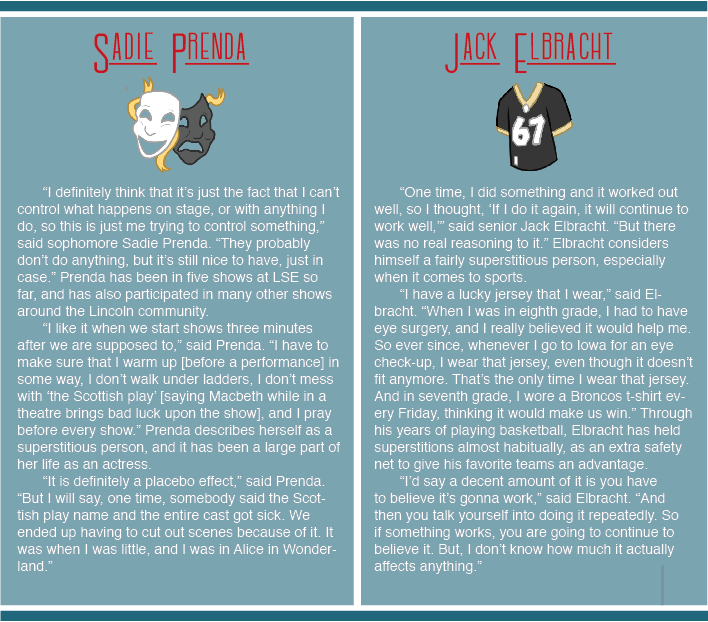

Superstitions, filled with mystery and seemingly pointless attributes, have survived the test of time to still have relevance today. There are some that have been used for hundreds of years and have become part of the common culture – like saying “bless you” – and others are specific to certain people – personal beliefs that are intended to aid themselves in their ventures, like wearing a lucky jersey on the day of a big game.

But where did they come from? Why do masses of people assume that doing a series of disconnected tasks will somehow affect their lives? Many of these long-held superstitions come from a vast history of events that have built off of each other to form the superstitions we know today.

Whenever someone sneezes, it is common courtesy to say, “bless you,” seemingly as a way of acknowledging their sneeze or excusing them for their uncontrollable outburst. But there are actually quite a few different possible origins for the phrase.

Some used to think that a sneeze caused the soul to leave the body for a moment, so saying “bless you” was meant to protect the soul from demons. Others thought it originated during the Bubonic Plague, or Black Death, that wiped out much of Europe’s population in the late 1340s. People thought a sneeze was a sure sign of infection, and saying “bless you” was a way of commemorating their soul to God because they were beyond the help of anyone in the mortal world.

Another common superstition surrounds the day of Friday the 13th. The fear of Friday the 13th, called paraskevidekatriaphobia, also has many possible origins, with many of them rooted in religion. The idea of the number 13 being unlucky could be traced back to ancient mythology.

According to Donald Dossey, author of “Holiday Folklore, Phobias and Fun,” a Norse myth told of a dinner party for 12 gods at which a 13th guest showed up uninvited. The uninvited guest, the trickster god Loki, proceeds to stab the god of joy and happiness, Balder.

Another possible explanation is that Judas was said to be the 13th to be seated at the Last Supper in the Christian faith. Judas later betrayed Jesus, then took his own life out of guilt. It’s said that if 13 people have dinner together, the 13th to sit would die within the next year. Over time, the fear of 13 became more broad, causing people to fear the number so much that some buildings refuse to have a 13th floor.

Friday has also been considered an unlucky day in Western tradition. In 1882, poet John Godfrey Saxe published a poem called “The Good Dog of Brette,” about a poodle that roams the city with a basket, bringing donations home to his blind master. But on a Friday, a cruel butcher chops off the dog’s tail.

Another explanation, rooted in Christianity, is that Jesus was crucified on Good Friday. Both Friday and the 13th day of the month were considered unlucky, so the combination of them, rather than cancelling each other out, created a day of supreme unluckiness.

Why do people believe them? Do people think that some higher force will come smite them where they stand if they don’t wear their lucky headband for a game? Or is it more of a psychological factor?

Many think of it as a way to control things over which they would otherwise have no jurisdiction. It could also be a safety net. Something else to blame if things don’t go their way, or an advantage to aid in something they don’t trust themselves to be able to accomplish. Or it could just be something to believe in. Something that gives people hope for a future, despite possibly unlikely circumstances. The simple act of believing in these odd tasks could end up making some of them work. Like a sort of placebo.

But the honest truth is, no one knows if they actually work or not, and they most likely won’t be proven right or wrong anytime soon. So what’s the harm in believing? Just in case.