Our voices: What it’s like to speak a foreign language in the US

May 1, 2020

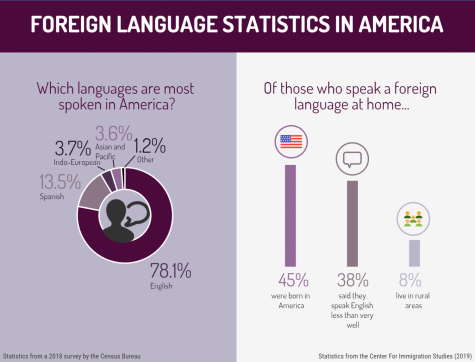

Some may say that the ability to speak multiple languages comes with the ability to see multiple worlds. You hear a mother and a child communicating in a foreign language in a store aisle, and various thoughts may come to your mind. You pay special attention to their gestures and expressions; factors that don’t really cross your mind in a normal conversation. Is it because you want in on their conversation? Is it curiosity that causes you to be flustered? Maybe it’s the fact that you can’t understand them that throws you off. Or perhaps, it’s awe that causes you to be so focused on their conversation. Being able to understand more than one language does seem impressive and a difficult task to do. However, does bilingualism really only come with benefits?

There have been some statements that suggest being able to speak multiple languages has advantages. For example, according to a 2016 article from The Atlantic titled, “The Bitter Fight Over the Benefits of Bilingualism,” by contributor Ed Yong, common benefits of bilingualism include advanced mental abilities, which allow for better control of thoughts and behaviors, such as focusing on a goal, ignoring distractions, switching attention and planning for the future.

However, the more hidden side of bilingualism is the inherent prejudice that polyglots, people who speak multiple languages, may face, and the inaccurate perceptions that come with it. To an outsider, hearing foreign languages comes with curiosity and oblivion. When people are faced with an unknown language, judgements become more focused on actions and gestures. Adjunct Psychology Professor Blake Eastman of The City University of New York sets the non-verbal component in interactions at between 60 percent and 90 percent.

What happens when another person’s perception of you becomes based solely on your identity? At Lincoln Southeast, there are many students who have grown up with multiple cultures, and thus, understand multiple languages. With a different sense of identity from others, they also face different experiences as well. Southeast students Sara Al-Rishawi (11), Dalena Mai (11) and Andrea Sanchez (9) are amongst many students at Southeast who speak multiple languages and share these experiences.

Al-Rishawi primarily speaks with her parents and family members in Arabic. Because both of her parents’ native languages are Arabic, she grew accustomed to speaking that language at home. Additionally, because she was raised by her grandmother who doesn’t speak English, the only way she could communicate was to use Arabic. Because of her long-lasting connection to her language, she perceives her culture as a positive influence on who she is.

“Culture is a huge part of my identity,” Al-Rishawi said. “The Middle East has a rich history, and being Arab, a lot of that history and tradition is still used and believed [in] today. My personality, beliefs and my character are more representative of my Arab side than my American side, and [that] is the way that I separate and identify myself in public settings.”

However, there have also been situations where Al-Rishawi has felt uncomfortable with others’ treatment of her.

“I do get treated differently, especially in settings with people that don’t exactly understand where I come from, or have negative biases towards Arabs [or] Muslims. [I] have been followed at stores by security, and get random checks by TSA,” Al-Rishawi said. “A school-specific example would be my participation on the tennis team. This treatment was not discriminatory by anyone on the team, but going to tennis dinners and being the only non-white person there, I can feel the awkwardness that the parents feel, as Arab hijabis are not common in the tennis world. [I] see that they are having conversations with the other girls, but then don’t really talk to me. It’s not that big of a deal and not that deep, but when parents shelter their kids too much from what is different, they end up sheltering themselves.”

Furthermore, as someone who grew up with both cultures, it may be hard to fit into both, no matter where Al-Rishawi is.

“I do try to balance the Arab and American culture as much as I can, and I have also been treated differently because I am American. In the Middle East, there have been instances where prices have been increased at shops because of the stereotype that Arab-Americans are rich, or I’ve been gifted things because I’m American,” Rishawi said. “No matter what culture I identify with, I get treated differently than those that are supposedly ‘native’ to it.”

However, Al-Rishawi does not feel ashamed of her identity, as her parents taught her the importance of sticking to roots, to have confidence in herself and to be proud of her heritage; principles that she dedicated herself to throughout high school.

“Up until high school, I didn’t really talk much about being Arab and tried to fit in as much as I [could], just so that I wouldn’t get ostracized, because everyone knows that middle schools are probably the craziest years of our life,” Al-Rishawi said. “I pretty much kept it on the back-burner until high school, when I did not care for people’s opinions and just embraced where I came from.”

Dalena Mai, a junior at Southeast, has also grown up with a close connection to her language and her culture. Because both of her parents are from Vietnam and speak broken English, she finds it easier to communicate to them in Vietnamese. She was exposed to this language at a young age, and her mother made sure that she knew her heritage wouldn’t become too westernized or forget her roots as she grew up in a western society. Because of this, Mai has grown to love her culture and be proud of her identity.

“Culture is a huge part of my identity. My life really revolves around Buddhism and the culture of Vietnam,” Mai said. “The clothes, food and celebration make me feel good about being a Vietnamese-American.”

However, there are many stereotypes about her culture that show up in her daily life. Two of the most popular misconceptions are that all Asians are rich with plenty of high-end items, and were born smart, but Mai says that those stereotypes aren’t applicable to everyone.

“My parents came from Vietnam, coming to the U.S. in 1994. They worked hard to get where they are today. The things I have are because of my good grades and what-not. People see me wear name-brand clothes and that I have AirPods, and they put me onto this pedestal,” Mai said. “Quite frankly, it’s annoying. Another misconception that I hate is that all Asians are smart. Some struggle more than others, and I don’t like it when people group us together.”

However, these stereotypes don’t change how Mai feels about her culture. In fact, she thinks that being able to speak another language certainly comes with many advantages, and one of those benefits confirms many people’s greatest concerns toward polyglots.

“I don’t really mind speaking Vietnamese in public because you can basically trash talk the other person right in front of them, and they don’t even know it,” Mai said. “It’s fun because sometimes people are really rude to you for speaking another language. I also get treated differently by other Vietnamese people. If my family goes to any Vietnamese-owned place, they always give us discounts. It’s basically Asians sticking together. I have never felt ashamed of myself. There was no need to be ashamed, because everyone is different.”

Southeast freshman Andrea Sanchez is fluent in both Spanish and English, but she finds that these two languages can collide with one another. Spanish was the language that she was taught at birth, and she first started to learn English when she started elementary school, where she was put in the English Language Learner (ELL) program to get assistance on speaking and understanding the English language. At home, she used to only speak Spanish, but when her sisters learned how to speak English, she had to adapt to this new language as well.

“This does have issues though, since I speak less Spanish than I used to,” Sanchez said. “I’ve started to forget how to speak it now, so I take Spanish classes so I could be able to use Spanish at school and improve it as well.”

However, just like many other students that speak multiple languages, Sanchez also points out that there are noticeable misconceptions surrounding her language and culture.

“I’ve heard that people stereotype us as lazy, criminals, high school dropouts, drug dealers and so much more, when these just aren’t true,” Sanchez said.

Despite this fact, she still embraces her culture and speaks in her native language in public without hesitance. She’s seen cases where people were told that they shouldn’t speak their native language and that they should only speak English in America, but she doesn’t falter to the discrimination against her ethnicity.

“My culture is a large part of my identity. Religion, music, language, ancestry, food, history and more are part of everyone’s culture and shape people’s identity. I haven’t really felt ashamed of who I am, but due to racism and hatred toward Hispanics, it did make me sometimes have second thoughts,” Sanchez said. “When Trump was running for president, he said, ‘They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists, and some, I assume are good people,’ towards the Mexicans.”

However, Sanchez acknowledges that some people may feel this way, and she did not let these thoughts bring down her views on her culture.

“This made me realize that it doesn’t matter if they met me or not, there are people who really hate me because of my race, ethnicity and culture. But other people’s opinions don’t matter to me, because it’s dumb of them to hate others based on stuff like that,” Sanchez said. “So, I’m not ashamed of who I am.”