#MeToo:The hashtag started the conversation in our country, but what about in schools?

November 9, 2018

HOW #METOO BEGAN

Conversations about sexual assault and harassment exploded with the #MeToo Movement in mid-October of 2017. But the phrase “Me Too” was first used on MySpace in 2006 when activist Tarana Burke founded the movement to empower other women to speak out about their experiences. Now, over a decade after Burke’s first “Me Too” post, this hashtag has led to over 8 million people responding to the movement with their stories.

Alyssa Milano was one of the first celebrities to add her voice to the #MeToo movement. On a Twitter post, Milano said: “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted, write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet.”

Milano had always been involved in the political empowerment of women by posting on the political website ‘Patriot not Partisan’, but wanted to do more to help the cause, which led her to posting the #MeToo hashtag. “The movement itself has become something that is in the hands of millions of women throughout the world,” she told The Guardian in an editorial article, “and they will continue to move it forward.”

But Milano is not the only celebrity to use #MeToo. Others include Rosario Dawson, Molly Ringwald and Reese Witherspoon.

While it may be easy to view these stories in the abstract – as terrible things that happen to other people in places far away from home – the fact is that sexual harassment, abuse, misconduct and assault is present in all communities.

Even in Lincoln. Even at Southeast.

In fact, nearly half of students in grades seven to 12 – and more than half of girls overall at that level – reported experiencing some form of sexual harassment in the 2010-2011 school year, according to research from the American Association of University Women.

But finding this data is hard. Due to rampant underreporting – by students themselves and by schools and school districts – the epidemic is often over- looked at the K-12 level.

Data collected by the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights for the 2013-2014 school year show that more than two-thirds, or 67 percent, of local education agencies reported zero allegations of sexual harassment or gender-based bullying. And according to 2014-2015 school-year data on student victimization by the National Center on Education Statistics – the statistical arm of the Department of Education – there were approximately zero reports of sexual assault or rape among students ages 12 to 18.

CLARIFYING CONSENT: WHEN “NO” IS IGNORED

Senior Helen Howard never thought something would happen to her, so when she and a friend were hanging out and things started to escalate, she was surprised and caught off guard.

Howard was able to recognize what was happening, that she didn’t want it to happen, and stopped it. She said this was an eye-opening experience for her and that she learned just how quickly things can get out of control.

“I don’t think people understand how significant [and impactful] those seemingly short incidents are and how much they can affect the way you think after they happen,” said Howard.

While Howard was able to take control over the situation she was in and say “no”, this is not the case for many women.

In an article titled “Why Women Have a Hard Time Saying No”, the author claims that women struggle with ‘no’, especially if they think someone’s feelings may be at stake or if they think they’ll not be liked.

“Despite what most women think, this is not some immutable gene or biological defect,” writes the author of the article, KathrynJ Lively Ph.D. “Rather, it’s actually a socially learned coping mechanism that can, with a little time and attention, be unlearned.”

Another LSE student, Kaylie* (not their real name), said saying no was hard because she thought that the relationship would be at stake if she denied her partner. “I was so caught up in the thought that ‘Oh my god she might break up with me’, that I just let it happen.”

Lively writes that women need to practice saying “no” because it is not an interaction in which they are totally comfortable or confident.

And yet, feeling confident in the ability to say ‘no’ does not guarantee that the act of saying it will thwart unwanted advances. The partner must recognize and respect the ‘no’. This was not the case for Kaylie.

“I didn’t really feel like at the time I was being used, but then when I would go back and think about it after we were done, I would realize how much I actually said no to things that still happened.”

Kaylie’s experience and the problem with “no means no” fall into a larger conversation about the missing piece of sex education in Lincoln Public Schools: Consent.

While the phrase “no means no” itself is a legitimate slogan, it doesn’t really provide a complete picture of consent because it puts the responsibility on one person to resist or accept an activity. It also makes consent about what someone doesn’t want to do, instead of being about openly expressing what they do want to do.

But, luckily, LPS students are now getting this explicit instruction on how to have these conversations.

Sexual health education in LPS begins in 7th grade with education about the male and female anatomy, puberty, abstinence, reproduction, and sexually transmitted infections. In 8th grade, the curriculum stresses abstinence from sexual activity but, according to LPS Health Education objectives, “the curriculum goes beyond the abstinence-only message and provides students with age-appropriate information regarding the prevention of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV/AIDS, and unintended pregnancies.”

In high school, the curriculum covers an array of topics concerning sexual health, including “Violence in Schools”, “Responsible Relationships”, “Dating Relationships”, “Unhealthy Relationships” and “Sexual Issues in Society”. The objectives for these units is for students to be able to:

♦ Describe effective ways to reduce bullying, hazing, sexual harassment and hate violence.

♦ Explain the relationship between a need for control and violence.

♦ Identify reasons why a person should report a rape

♦ Explain the effect of sexual abuse on a victim

♦ Describe an effective way to reduce sexual harassment at school

Consent, according to the nonprofit program Sexual Assault and Intervention Services, is when partners mutually agree to sexual activity. This can include hugging, kissing, touching or sex. And, as is stated on the group’s website, consent is not simply granting permission for a particular activity. For consent to truly be given, it must be affirmative. Also, just because someone consents to something one time, it does not mean that they will always consent. Consent must be given each time and a person can always change their mind.

Even though consent is not currently taught in all high schools across the country, that doesn’t mean it won’t soon be added to lesson plans. Matt Avey, the Curriculum Specialist for Health and Physical Education, said that health educators are always looking for ways to enhance their courses in order to keep students safe and reduce risky behaviors. Thankfully education about consent is taught in the LPS curriculum and at Southeast.

“Obviously the #MeToo movement has shed a lot of light toward the topic

of consent and sexual harassment,” Avey said. “There are a number of topics in the news that are related to Health Education. Typically these topics provide our Health Steering Committee and myself an opportunity to reflect on our current practices and curriculum and see if there is anything we could capture to enhance our curriculum when these topics come up.”

LSE Health and PE teacher Caitlin Gray says that she talks to her classes about consent even before they get to the units on sexual health and then they go over it numerous times and in different units.

“We [even] had a presenter come in from the ‘Set Me Free Project’ and they talk about consent, and it is a two-day presentation,” Gray said. “We talk about consent even when it comes to not just sexual intercourse, but boundaries as well.”

Gray said that her and her fellow health educators are always finding ways to adapt their curriculum to the changes in our culture. Part of the changes recently included changing the health unit to a whole semester.

“The district is going to develop the curriculum and try to improve it.”

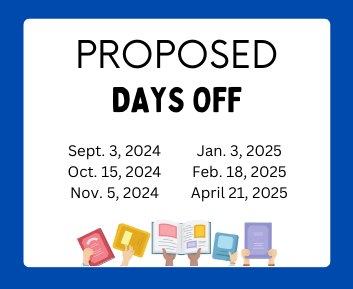

Avey said that the a curriculum revision will take place in 2020.

ABUSE IS NOT JUST PHYSCIAL

Education on sexual assault, harassment and consent is vital to the health and well-being of students. But so is information on the unseen side of relationship violence – the emotional and mental toll it has on victims.

In 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted an extensive survey on sexual violence and found that nearly half of all women and men in the United States have experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime.

LSE senior Katherine* said she was in a mentally abusive relationship that took a toll on her mental health.

“He would push me to do stuff with him. He would flip the situation and make everything seem like my fault. That I was the bad person in the relationship and everything I was doing was wrong. I would ask myself if I wasn’t good enough for this person.”

It took a while for Katherine to realize that this was not a healthy relationship to be in. “I had to talk to so many people before I could get the courage to get out of that situation. But I ended up getting out.”

Katherine now wants others to know that they can stand up for themselves and get out of abusive relationships. “[It’s] not worth you being abused in a certain way or you hurting all the time and second guessing yourself all the time.”

REPORTING LEADS TO EMPOWERMENT

So what should students do after they’ve been a victim of sexual harass- ment, assault, or been in an abusive relationship? LSE Social Worker Morgan Young says students should first find a trusted adult in the building and report the incident.

“[After] a student discloses sexual assault, we will first listen to their story,” said Young. “We try very hard to not ask the student to repeat their story multiple times or to include multiple people.”

Young said that part of her job as a social worker is to make students feel comfortable and safe enough to tell their story. After the initial report, she works with the student to determine next steps, such as involving the student’s administrator and the School Resource Officer or talking with parents.

“If a student discloses that they were assaulted by a peer then it would be the decision of the family to determine whether or not to report the assault to the authorities,” Young said. “Families can always consult with our School Resource Officer to help make an informed decision. Similarly, [I] understand that

sharing [a] story with parents can be very difficult so [I] also help the student to figure out how to share their story with their parents.”

After these initial conversations, the student will work with their counselor and/or social worker to develop a plan moving forward to ensure that the student is supported and that any other mental health needs are addressed.

Additionally, Young says that at some point, traumatic experiences will eventually come out; this might occur as an emotional response in college or as an adult.

It wasn’t until Kaylie* left the abusive relationship she felt trapped in that she finally realized what had been happening. “It made me feel helpless and awful. I feel like there are definitely other people out there who are feeling the same thing, who are like me, who are too scared to say anything about it.”

Finding the courage to talk about a traumatic experience, such as sexual assault, is extremely difficult. But Young says that reporting can be empowering for a victim.

“What we find is that after you report and you come out on the other side of the experience, it feels better and empowering. People also feel empowered after the experience because they could have potentially reduced the chances that another person could be assaulted by the same individual.”