To Vax, or Not to Vax?

The reasoning behind COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy

December 10, 2021

For many people, the Spring of 2020 marks the beginning of the “before”. The time before COVID-19, before quarantines, before mask mandates and mass fear. Spring of 2020 was was when life got flipped upside down. Businesses and schools shut down, people were isolated in their homes and hospital beds filled up as death tolls climbed. Scientists and doctors around the country were in a mad dash to find a solution. On Dec. 11, 2020, the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine came out for emergency use only, and was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for all people 12 and up by Aug. 23, 2021. And just recently, Oct. 29, 2021, it was made available for ages five to 11.

Many thought this was the end of the pandemic and life would finally go back to normal. However, numerous people in the United States (US) didn’t seem to have the same sense of urgency as they previously did.

Since the vaccines had come out, rising suspicions of the effectiveness and safety of these injections has created hesitancy to get vaccinated.

Clinical Pharmacist at Bryan Health Katie Packard says there are many reasons for this, mainly stemming from fear or misinformation.

“There is the misconception that the development was rushed and not studied long enough. That is simply not true,” she said. “Most vaccine adverse effects occur within the first two months after injection, and all three vaccines used in the US have been studied much longer than that.”

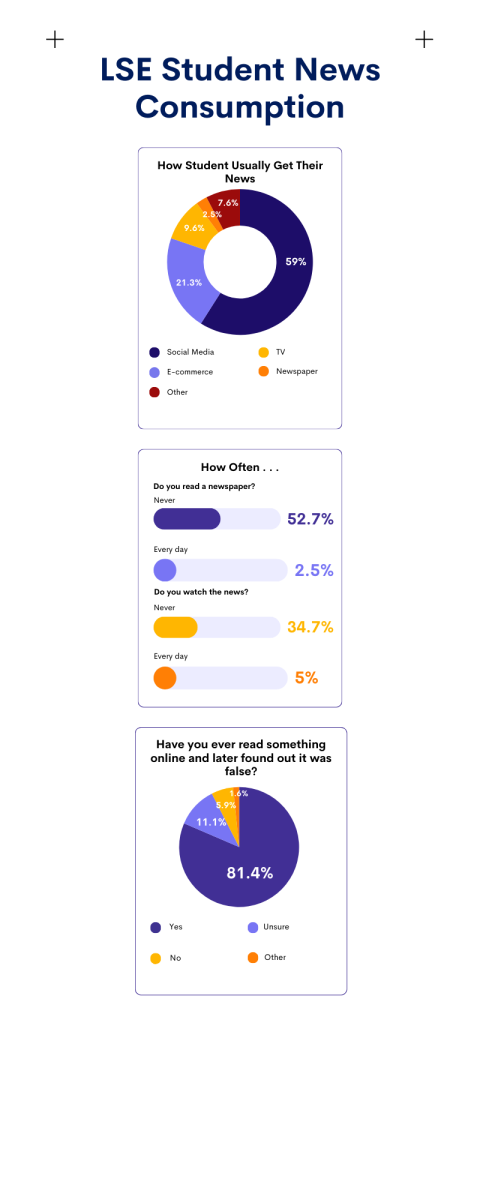

Packard believes that social media has played the largest role in vaccine hesitancy.

“False information spread over social media such as vaccines containing microchips, magnets, or causing infertility or sterility is simply false information. Sadly, incorrect information has been used by some as tools to manipulate people’s opinions for personal or political gain,” she said.

As of right now, 59.4 percent [and counting] of people in the US are fully vaccinated, and 57.4 percent of Nebraskans are.

In a survey of 201 Lincoln Southeast High School (LSE) students, 17.3 percent of respondents said they did not have the COVID-19 vaccination, and didn’t plan to any time soon. The reasons as to why they didn’t want to get it fell under three main categories: questioning the safety and effectiveness of it, feeling as though COVID-19 isn’t a big enough risk or parents’ political affiliations.

But for the 74.6 percent of people who said they were fully vaccinated, most believed it was necessary to protect oneself and others, or thought it would be a way to bring back normalcy.

As for the remainder of unsure respondents, many said they just wanted to wait a little longer due to fear of such a new and quickly developed shot.

Sophomore Josiah Welch has chosen not to get vaccinated due to a number of reasons, similar to many of the LSE survey respondents.

Welch says the intermixing of politics with modern science has created him and others to question the reliability of the COVID-19 vaccines.

“The vaccines have been heavily politicized,” Welch said. “So many massive corporations and the government have taken to be forcing it on us and that is super suspicious.”

Welch says that the two polarizing sides–with one seemingly discouraging vaccination and the other urging for it– has caused him to abstain from getting it at all.

There also appeared to be a trend of students receiving or not receiving the vaccine as a result of their parents’ decisions.

Welch says that even if he ultimately decides the vaccine is safe, he still would most likely not get it out of respect to their beliefs. He says that he has a “really strong connection with [his] family and doing that would almost undermine them.”

Medical professionals and doctors have also noticed something known as “The Great COVID-19 Irony”, which could also be playing a role in the absence of vaccination in certain groups.

“Vaccinated people may overestimate their peril, just as unvaccinated people may underestimate it,” Surgeon General Vivek Murthy said in the Politico article “Why We Can’t Turn the Corner on Covid”.

A number of national surveys have shown that unvaccinated people are much less likely to fear the virus than vaccinated, and are additionally less likely to be willing to wear a mask.

Many choosing not to get vaccinated just simply don’t believe it’s a big deal or that it would affect them greatly if they got COVID-19.

“I’m young enough, and I’m not in too much danger of getting horribly affected by COVID,” Welch said.

Packard disagrees with the statement. She hopes that many will keep in mind the dangers they could be in when making the choice of whether or not to receive the vaccine.

“Almost all patients we see with severe COVID-19 disease that cause them to need ventilators, suffer long term effects or die at Bryan Health– and nationwide– are unvaccinated,” Packard said. “All ages are being affected now. Not just the elderly or sick.”

Packard believes that no matter one’s opinion on the COVID-19 vaccination, the facts and statistics can not be disputed.

“While no vaccine prevents 100% of its target disease, it is clear that the vaccine works well to prevent severe disease and death,” Packard said.

Recently, talk of mandating vaccination has caused a great uproar around the nation. Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, mandatory vaccination has been a tool in combating illness for years. There are already many mandated vaccines for diseases such as measles, mumps, rubella and polio, so Packard believes it is not unreasonable to mandate this one.

“Making a fully FDA-approved vaccine mandatory in situations where other vaccines are mandatory such as public schools, colleges, camps, healthcare, assisted living situations and etc is reasonable and is one tool in our arsenal to prevent severe illness, hospitalization and reduce viral mutation,” Packard said.

Packard believes that in order to get the nation out of this pandemic, mandating vaccination is one of many actions needed to be taken.

“I think that mass vaccination is one very important tool to help get us out of the pandemic,” Packard said. “That is in addition to taking precautions like mask wearing, handwashing and social distancing when possible.”

Author and Professor of Psychology David Myers uses a psychological concept called cognitive dissonance to explain why mandating vaccinations could work. Cognitive dissonance is the idea that attitudes will follow behavior. Just like how seat belt mandates–a widely agreed upon idea– first received angry defense on personal liberty, Myers believes it could happen similarly with vaccines.

“Here in Michigan, the state representative who introduced the state’s 1982 seat belt law received hate mail, some comparing him to Hitler—despite abundant evidence that, like today’s vaccines, seatbelts save lives,” Myers wrote in his article “The Social Psychology of Vaccine Mandates”. “But time rolls on, and so did seat belt acceptance with Michiganders’ approval of the law rising to 85 percent by the end of 1985 and usage rising from 20 percent in 1984 to 93 percent by 2014.”

Eventually things will have to improve, one way or another. Pandemic life will not last forever. Political figures are being pressured now more than ever to make a decision. But whatever choice is made, whether to mandate or not to mandate, they can’t please everyone. One side will always be unhappy in the end. All they can base their decisions off of now, is what will inevitably be for the greater good. For now, the decision to receive the COVID-19 vaccination is optional, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advises that people continue to practice social distancing and mask wearing, especially if unvaccinated. Packard believes that if everyone continues to take precautions advised by professionals like herself, there will finally be a chance for a complete return to normalcy.